Response: Father

“make pretend ashes out of burned photographs of him”

In our monthly Response Column, NAILED asks readers to respond to a particular word or topic. We are seeking raw, honest personal responses that aim less to answer questions and more to raise them. Responses in the form of art, photography, essay, story, poem, and rant will all be considered for publication. July’s topic is BREAKUP, please email your responses to Kirsten@NailedMagazine.com by July 2oth, for publication at the end of the month. (Word count limit: 1,000 words.)

+ + +

Response: Father

Ashes and Afterthoughts, by Nicola Anaru

When my father died earlier this year, it was not a tragedy so much as a waste. They say that alcoholism is a battle, but my father didn’t so much as mutter under his breath, let alone put up a fight.

Bottle to lips, cradle to grave; his addiction was a proxy for terminal anger, terminal sadness, terminal boredom. It must have been damn boring in the end; by then his athletic frame had swollen, his bruised, puffy legs no longer able to support his weight. He curled his anger inwards, refused visitors, and shrouded his condition in secrecy.

Each morning, his wife would set a six-pack on his bedside table. When night fell, she gingerly placed a bucket by the bed, to catch the spurts of blood that gushed from his mouth in the darkness.

My father did not want to be remembered. He left no inheritance, expressed no love, no regrets.

My name was tattooed on his arm, as if I was something that happened to him and left a scar. We regarded each other warily; he with a mild curiosity, and I with a simmering resentment for the negligence of his four children.

His fifth child was introduced to us at the funeral, who wanted nothing to do with the rest of us and left shortly afterwards. Like father, like son.

Bereavement had cracked me open by then anyway, taut fists wiping away salt water. None of us children were mentioned in the eulogy, we had been erased even as we diligently sat in the front pew. I keep learning and unlearning how very little I matter, how so much I am cared for comes from those in my circle.

How do you mourn the loss of someone you have never had? My own grief is unsteady, background noise at a frequency I cannot always hear.

I went to his house to beg for mementos to pass on, my sole effort to be useful as the eldest child. His wife gave me a few belongings in a plastic grocery bag. I examined each of these in turn – his wallet, wristwatch, and a couple of rugby jerseys. As thankful as I was to be able to present these treasures to my grandmother, they brought me no comfort.

No keepsakes were necessary to recall that in life, he had no child support, no time, and no warm embrace to offer me. I was less than an afterthought, he a small pile of ashes to be scattered in my absence.

+

Nicola Anaru is a writer and artist residing in the Pacific Northwest. Her work has appeared in Cirque, and she is an alumni of the Voices of Our Nations Arts Foundation (VONA) memoir workshop. She is learning to value her own voice.

+ + +

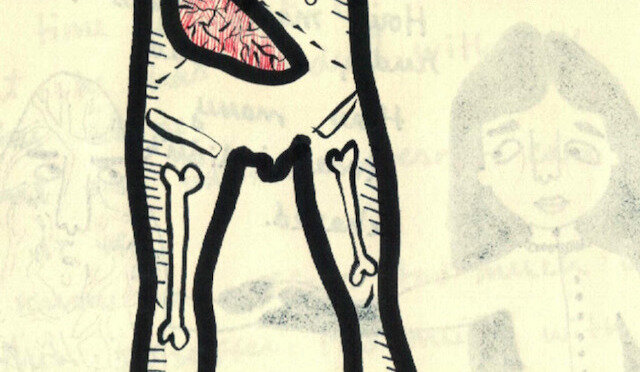

The Father Incident, by Bárbara Moura

Bárbara Moura graduated in Film at the National Film School of Portugal and then moved to London where she did her MA Applied Imagination in The Creative Industries at Central Saint Martins. The main connection between her subjects is herself, as she believes we are our own biggest case of study. Her illustrations focus on emotional experiences personalized by characters that are essentially self-portraits. She is currently working on the illustrations for a book of feminist poetry aimed to raise money for women’s charities and women who were victims of sexual slavery.

To view her artist feature for NAILED and a gallery of her art, go here.

+ + +

Another Sunday, by Negesti Kaudo

Yesterday was Father’s Day. I know I’m not the only young woman alive without a father to celebrate. I know that my sister and I are not the only ones sitting around in the house watching Netflix and pretending as if it’s just another day. And I know we’re not the only ones who have forgotten about the holiday for so long that each year it seems to be slammed into our faces harder than before.

This year it was more important than ever, but it’s been thirteen years since the last time I celebrated. It was Father’s Day in my email inboxes, on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, the radio and television. Everyone had barbecues and Sunday dinners and church picnics…I had my thoughts. I was accosted by photos of my friends and their fathers, their grandpas, their uncles, and while I scrolled through the photos and cliché captions on posts their fathers may never see, I wondered if I should post one. If I should get the stepladder and dig through the foyer closet and look for an old Polaroid of me, my sister and our daddy. I wondered if it would be appreciated, or if I’d just be the fatherless girl bringing down everyone’s good vibes. I didn’t post a photo.

What do we do on Father’s Day for those of us who don’t have the privilege to celebrate with them? I taught my sister how to deep-condition her hair and spent the day watching Scandal. It’s just the two of us – the only full-blooded siblings in the family – and we don’t talk about our dad too much. I wonder when we both grew out of the phase of calling him “Daddy” and began to refer to him as “Dad” or “my father” in my case. And I wonder if she thinks about him as much as I do, I think she does, but in different ways. She thinks about the man we never had the privilege to know and what he did before us and I think about the man we knew and try to piece together an image of him before he got sick, before the cancer, and before April 11th.

Thirteen years ago, a few days after his death, we visited my father’s house on Leonard Avenue for the last time. Houses lined only one side of the street, each yard sloping upwards to meet its foundation. We walked up the stairs, and I noted the bean tree weighted down with ripe green beans and the piece of green siding on the house that was hanging after being stuck by lightening. The wrought-iron screen door welcomed us in and behind it hung the Ethiopian flag, the lion of Judah allowing us entry into an empty home, a cluttered home, one packed with memories. We were there to take some of the memories. My dad was an artist, so we took an oil painting and a wooden statue. I took two things. I ignored my yellow bucket of thrift store and vintage toys for a bound Lion King lyric book and from the fireplace, I took a framed photo of me and my dad and it was mine, not my mother’s, not my sister’s, mine.

In the photo, his dreadlocks are long and a combination of thick and thin, traveling down to his waist. The dreads on his beard hang low enough to cast a shadow on his bare chest. Dreadlocks hang in front of the Ethiopian cross hanging around his neck, silver on his sternum. He has light brown skin, like dark honey or black tea that hasn’t steeped for too long and there is a tattoo on his arm. I’m sitting upright in his arms, carefully being held, and his ringed finger holds onto the front of my onesie. My dad is staring down at me in his arms, in my yellow onesie, but I am staring at the camera or behind it at my mother who is most likely behind it. This is the moment: father-daughter pride, father-daughter love, a moment that cannot be recreated or realized until too late.

And two months later, after we’ve left the house, and the funeral has happened, and we’ve finished out the school year, two months later, my sister and I sat at a half-day neighborhood summer program and made Father’s Day cards with the rest of the children. We drew dreadlocked little girls and a dreadlocked man. We wrote “Happy Father’s Day” and “I love you” and “I miss you” and we took the cards home. In a corner of the living room, my picture sat on the floor, leaning on the wall and sunshine streaked across its glass-less frame. We tucked the two cards in the back of the frame and never said a word and there they sat, for years, becoming discolored and remaining unread.

When I was eight years old, I stopped celebrating Father’s Day.

+

Negesti Kaudo is a twenty-one-year-old, Midwestern girl who indulges in writing raw. A recent college graduate, she intends on pursuing her MFA in Creative Writing in the fall. For now, she's currently working on getting adulting "right" and writing down the stories that emerge from it.

+ + +

The Pilgrims, by Daniil Maksyukov

Daniil Maksyukov (1995) is an emerging street photographer living and working in Russia. Although photography is currently a hobby, he would one day like to make a life long career in documenting Russian life. He has achieved recognition and several awards for his work and is most passionate about candid shots, capturing the truth and pulse of life in the streets around him.

To view his photo essay "Junk and Gems" for NAILED, go here.

+ + +

Sunday in My Father's House, by Hollye Dexter

The thwack of the daily paper on the front porch announces the start of a new day in my father’s house. Slivers of morning sun squeeze through the blinds, always shut tight. A caged bird screeches against the drip and hiss of morning coffee brewing, while a candy-apple cardinal feeds freely outside the window. The shuffling of slippers, TV news and gospel music is our cacophonous morning song. A fog of cigarettes and something frying in the kitchen settles over me like a blanket. Glenn Beck rants from car radio speakers as we head out for Sunday church services where my family, two gay and one ex-con, will all be Baptists for an hour and ten minutes.

At midday, the Texan sun overthrows the clouds, summoning youngsters outdoors to ride bikes and catch balls and tattle on each other while cicadas and jaybirds compete to be heard and dogs meander then curl around our feet. Dad and I sit in lawn chairs talking, as we always do, about God, politics and prison. Ru Pauls’ Drag Race blasts from the TV inside where my brother gives haircuts on the kitchen linoleum.

Humidity rolls in from Galveston as the sun fades in a blood-orange sky. Phones ring, dogs bark, the back door swings opens and shut as kin stop by bearing Texas-sized pecan pies and Bluebell ice cream. Dad’s Jambalaya simmers on the stove. We siblings sneak margaritas then hide the tequila from him. Harsh words and tender exchanges will take place in this kitchen before we hug goodnight, accepting the way it is, and who we are.

All is still but for the blare of five televisions tuned to different channels. I am lulled to sleep by the low hum of factories steadily pumping their toxins into the night sky. A low and mournful train whistle punctuates the stillness, reminding me that soon I, too, will be leaving. Jesus hangs solemnly on his cross over the kitchen sink, eyes closed, expressionless.

+

Hollye Dexter is author of the memoir Fire Season (She Writes Press, 2015) and co-editor of Dancing At The Shame Prom (Seal Press)– praised by bestselling author Gloria Feldt (former CEO of Planned Parenthood) as “…a brilliant book that just might change your life.” Her essays and articles about women’s issues, activism and parenting have been published in anthologies as well as in Maria Shriver’s Architects of Change, Huffington Post, The Feminist Wire and more. In 2003, she founded the award-winning nonprofit Art and Soul, running arts workshops for teenagers in the foster care system. She currently teaches writing workshops and works as an activist for gun violence prevention in L.A., where she lives with her husband and a houseful of kids and pets. www.hollyedexter.net.

+ + +

Untitled Painting, by Shawn Huckins

+

Shawn Huckins (1984) was first introduced to painting after inheriting his grandmother’s oil painting set at a young age. As an adult, it’s taken a route through studies in architecture and film, plus a stint living on the other side of the world, for him to gravitate back towards art. Since graduating from Keene State with a major in Studio Arts, Huckins has taken inspiration from 18th Century American portraiture to 20th Century Pop Artists and preoccupied his work with a contemporary discourse on American culture. He currently lives and works in Denver, CO.

To view his gallery artist feature for NAILED, go here.

+ + +

Hoarding Halvah, by Rochelle Newman

I am your daughter. You taught me how to hold on to a newspaper clipping as if it held a secret piece of a puzzle. Every scrap of paper a clue. Precious evidence and supporting material stored for an investigation. I watched you file away our histories. The drawers in your desk and the dark moss green Pendoflex folders created hammocks of information. They were packed so tightly not another thing could make its way in.

I yelled at you for not letting me get rid of your beyond-a-shadow-of-a-doubt junk mail; even mom’s junk mail. A postcard from the drycleaner saying “We Miss You.” Of course they missed her. We all missed her. She had been dead for twelve years. When you weren’t looking, I scooped up envelopes by the pound, keeping an eye out for the ones with a life of their own. The ones you covered with your handwritten scrawl. A random letter, bill, or Publisher’s Clearing House solicitation, covered with reminders, dates, reference information. Selected out of hundreds, you established a relationship with certain pieces. You made it virtually impossible to throw those away.

“The caregiver says I left the stove on. But I checked it with a match. I was a boy scout. I know how to check for gas. She is making things up. I have been using my stove for many many years. I use wooden matches to check for gas. She says that’s dangerous. I was a boy scout.”

The other side of the same envelope read:

“Helen came today at 6:45. We went to the Grove. We had a good time.”

I look for clues. Ways of understanding who you were, what you were going through when I was little and when I wasn’t. You were always a mystery. It would be too easy to point to the effects of aging, of memory loss, of early onset Alzheimer’s. The loss of your wife, my mother, the loss of your independence. Too easy. The scribbling notations on scraps of paper, furious writings that captured your concerns; concerns you would articulate over and over again, draft after draft, until you thought you had stated it or supported the idea as clearly as you possibly could. That’s always who you were. It just became more senseless as you aged.

Women are taught that they will become their mothers. They don’t warn us that we become our father’s too.

+

I named them time capsules. Purses stuffed with random papers, business cards, pens and receipts. These purses hold items of little use and growing piles of change. They hold a moment in time. I retire these purses with their contents intact. I save time by not sorting through the contents. I save time by not worrying about things I might need when and if I might need them. Things will be there.

Perhaps that’s the logic you used when you left my mother’s clothes and shoes frozen in time. Untouched. Unmoved. Perhaps your time capsule is stored in a closet instead of a purse. Or on the bureau? There was the wig my mother wore during the worst of her cancer years. Before her hair grew back. “Better than it had ever been,” as she would say, always looking for a bright side. You wouldn’t let any of us touch that wig and make it go away.

“It was your mother’s,” you warned us whenever anyone suggested it was time to throw the wig away.

“It’s not hurting anyone there,” you insisted, thinking only of yourself.

I judged you harshly as I piled my own piles and created my own time capsules without the scrutiny of a daughter to condemn me as old, forgetful and foolish. Perhaps that’s why I never had children. They’re quick to judge but not quick to look in the mirror.

+

I’m not sure what I thought I was going to find when I landed on the Bank of America checkbook box. The kind they use to mail checks to your home when you run out. I’m sure I must have been looking for secret treasure, a bar of gold, or a secret stash of wealth that only you knew about. I lifted the top of the box with care, pulling up ever so slowly, until the contents were revealed.

Halvah. You had taken a half eaten bar of halvah and made it fit quite comfortably in that cardboard Bank of America box. You stored it beneath your mattress, on what would have been your side of the bed if the other side had still been taken. Part of the red and white crinkly plastic wrap was still there, with the moustachioed, turban wearing Joya Candy man smiling knowingly, protecting the chocolate covering that clung to the chalky, oily bar of Halvah itself.

What power did you have over me in your death that would make it impossible for me to part with this hidden Halvah? I put it aside, certain that it would only last as long as the clean up did, certain that it would come to a respectful but ritualistic ending as I bid it farewell and with it you. Days of cleaning. Purging and keeping. The Halvah remained intact.

In that unattractive, bland, brick of tasteless texture I saw your smile, all of your teeth--flossed daily and cavity-free, as you loved to say. I felt your big hands with their rough, square fingers tightly holding my little girl hand; wanting to hold my young woman hand only to be ignored. In that Halvah was the justified paranoia of an aging aerospace engineer, terrified of losing memory and memories. Terrified of having some stranger steal his Halvah or deny him that Halvah, as one would punish a child.

I held on to that Halvah. In doing so I held on to you.

+

Rochelle Newman is an MFA student at Antioch University in Creative Non-Fiction. An award winning playwright and stand-up comic, who leads a dual life as a US Hispanic marketing specialist, Rochelle is a frequent contributor to Advertising Age. Her literary work and interviews have been featured in NAILED, Lunch Ticket and other magazines. She is based in Los Angeles but always proud of her Lower East Side NY roots.

+ + +

Tug of War, by Alyssa Monks

+

Alyssa Monks, born in 1977 in New Jersey, began oil painting as a child. She studied at The New School in New York and Montclair State University and earned her B.A. from Boston College in 1999. During this time she studied painting at Lorenzo de’ Medici in Florence. She went on to earn her MFA from the New York Academy of Art, Graduate School of Figurative Art in 2001. Monks currently lives and paints in Brooklyn, New York.

To view a gallery and artist feature of Alyssa Monks, go here.

+ + +

Making Pretend Ashes, by Mo Daviau

My father was born in 1910; I in 1976. He died in 1992, when I was sixteen. A few years after he died, I found out that Antoinette, the star of many of the stories of his life, was still alive.

Antoinette was my father’s first girlfriend. By all accounts, he was loyal and loving and devoted to her. After he graduated from college, he returned to their tiny French-speaking town in Maine to marry her, and when he saw her after his time away, he realized he couldn’t. He’d changed, and she hadn’t, so he went back to New Orleans and married someone else. The last time they ever saw each was sometime in the early 1960s, over dinner somewhere in New England, their respective spouses in tow.

It was 2001, Antoinette was in her nineties, lucid and limber, worried about the day she’d turn 100 and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts would take her drivers license away. Me, in my twenties, the human representative of my father’s late life, on a mission to gather some crumbs of his life’s story. Strangely, I was embarrassed to meet her. It seemed improper to show a nonagenarian New England lady the hunger I had to mine information from the last living person who knew him as a young man.

“It was a long time ago,” she said of my father, because she knew I had traveled to her home in New Bedford to hear the stories. Her Boston Brahmin accent stretched those words into something more dramatic, like she was reciting a line from an old Bette Davis movie. I didn’t ask her about the man who did marry her, who stayed with her for sixty years, or their daughter, or the grandkids whose photos stood in frames around her house. I asked her about the man who’d left her, and me too, though under different circumstances at different ends of his life. “There was a lot of love there. He loved me very much. The Daviaus were a nice family. I remember that.”

She told me her stories. Some I remembered hearing from my father, some re-told by mother, others new to my ears. She took me into her bedroom, where the décor remained untouched since the 1950s, and opened the drawer to her nightstand. She took out the Tulane University bracelet my father had given her seventy years earlier, put it on her wrist one last time, and asked if I’d like to have it. I said yes.

Antoinette then pulled a small photograph from the drawer where she kept her treasures. “This was me back then. High school, when I was George’s girl.”

The round face, the hair that I assumed was brown, even though it was the black of a black and white photograph, the sweet smile of a French-Canadian girl in knee-high boots and a cotton dress. There was something familiar about young Antoinette. I had stumbled across one of my dad’s secrets, or maybe caught a nip of something in his subconscious mind. Would he, had we known each other as adults, have confided in me what I saw, or what I thought I saw, in Antoinette’s photo of her young self?

I didn’t say to Antoinette what I was thinking, because it was conjecture on my part. But the secret that I had partially made up in my mind based on that photograph, that he fell in love with my mother not because she was young, cute and told him she was in love with him in an uncharacteristically bold move, or because they shared a magical connection that transcended explanation, but simply because she looked like young Antoinette, which tugged on his nostalgic heart. In this version of his life, written by the daughter who, by the stretch in our years, he made a time-traveler, a reminder of his youth walked into his office in 1968 and asked for a job, and then his love in return.

I know I can’t know that for sure, but I’ve spent most of my life writing, if not about my father, then from the pain of his loss. Someone once recommended, since we never had a funeral for my father, that I hold a belated one now, and make pretend ashes out of burned photographs of him, to bury or spread in the sea. The stories about him that I make up based on faulty bits of information satisfy my desire for the real ones. I can’t have the real ones, just as I can’t have his real ashes. Even if what I imagine what drew my father to my mother isn’t true, that he fell for my then-twenty-year-old mother because she reminded my father of his first love, I’m going to keep it.

In a moment of candor, Antoinette said what I’d been thinking. “I know you’re here to talk about your father, dear, but remember, most of my life he was not part of.”

I said yes, Antoinette, I know. Me, too. And for the rest of the afternoon, we talked about other things.

+

Mo Daviau is a writer and performer currently living in Portland, Oregon. Her debut novel, Every Anxious Wave, will be published in February by St. Martin's Press. Follow her, here.

+ + +